5 another generosity

i enter an inviting blow-up art piece, investigate longtime nuclear warning messages, and consider what it means to offer openness in a time of fear

I felt as if I were visiting Disney World’s obscure, approachable cousin. A small child ran past me as I stood in line to enter a massive, breathing balloon-thing, an art piece set in a dark corner of an exhibit about possible futures.

We were at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The child’s father grabbed her around the torso and retreated, murmuring to her about lines and waiting your turn. She protested. We should have just let her cut, I think. I would want in immediately, too. I was in line, after all. I wanted to go in.

The piece: big, almost twenty feet tall and wide, glowing pink and then white, a network of air-filled bulbs. An exoskeleton of synthetic translucent material that covered smaller, more opaque bulbous shapes within. It reminded me of blow-up lawn decorations, but tauter and divorced from brand. '

It reminded me of a bouncy house, but cleaner, more beautiful, more ideal. I wanted to go in.

It reminded me of my mood. It was the weekend before my birthday, and I was under a lot of internal pressure to have a good time. I felt as if, to have a good time was to be a non-loser. It was newly 2020; I was determined to do right by myself. I was examining every single moment under the microscope of my attention, scouring it all clean for meaning. I kept feeling higher and higher, like a heady pink balloon. I was looking for a common thread to follow.

The art exhibit, called Another Generosity, felt like a fun-house reflection of me. I imagined that the lopsided balloons had been made, very quickly and among many hurried whispers, before I rounded the corner of the room, established for me to explore that feeling properly. There was white and pink light, as I mentioned before, and perhaps tones of yellow, but I couldn’t tell where the light was coming from. Light bulbs, yes—but they were hidden beyond the opaque shapes within. The entire thing breathed. There was air coming from small tubes that ran through the entire arrangement, inhaling slowly at seemingly random times, then pausing.

Photograph by Allison Denoble

“Gentle and respectful touches allowed for this object,” said the floor.

Okay, I thought, and grandly placed a hand on it. Touching the art made me laugh. The architecture was inviting. I wanted to know what it was.

This is what always happens, if we let it. Our curiosity drives us toward things. I am attempting to follow those impulses, to let my fear lie unindulged.

But what happens when that impulse is dangerous?

The Human Interference Task Force was a team of hard and soft scientists that came together in the 1980s to tackle the field of nuclear semiotics. In other words, the problem of warning ignorant individuals of the dangers of nuclear waste, particularly when the lifespan of scientific knowledge and language is but a fraction of the lifespan of life-threatening nuclear materials.

The problem—how do you construct a warning system that transcends culture? how do you store dangerous materials in a way that discourages curiosity? how do you anticipate the problem-solving skills of an exploring alien race?—begs to be answered with science fiction. I think of the terrific sci-fi film Arrival (2016), which addresses the question of translation when the Rosetta Stone must be constructed from square one. (Funnily enough, there was an installation of that film’s alien language artwork in the same museum room as Another Generosity.)

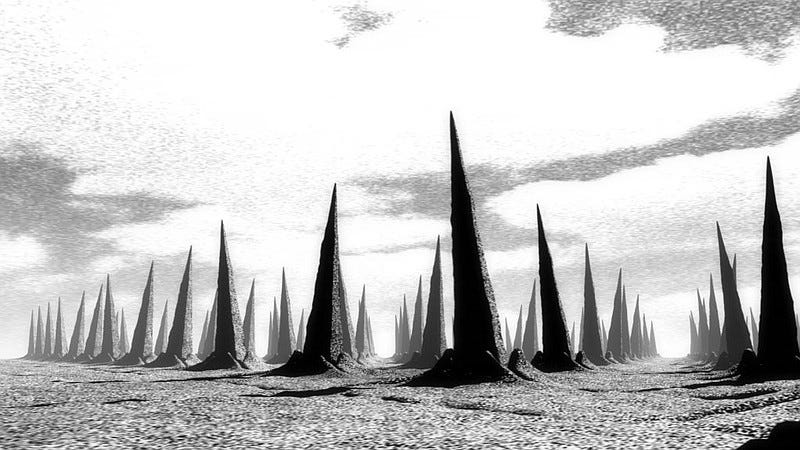

Some of these theorists proposed hostile architecture that would convey a nuclear waste storage facility’s lack of worth. Experts could design a facility that would bar all but those with high technical skills, effectively creating a kind of Dungeons & Dragons type puzzle with deadly isotopes as the treasure. The hope was that such an advanced people would understand nuclear waste’s threat.

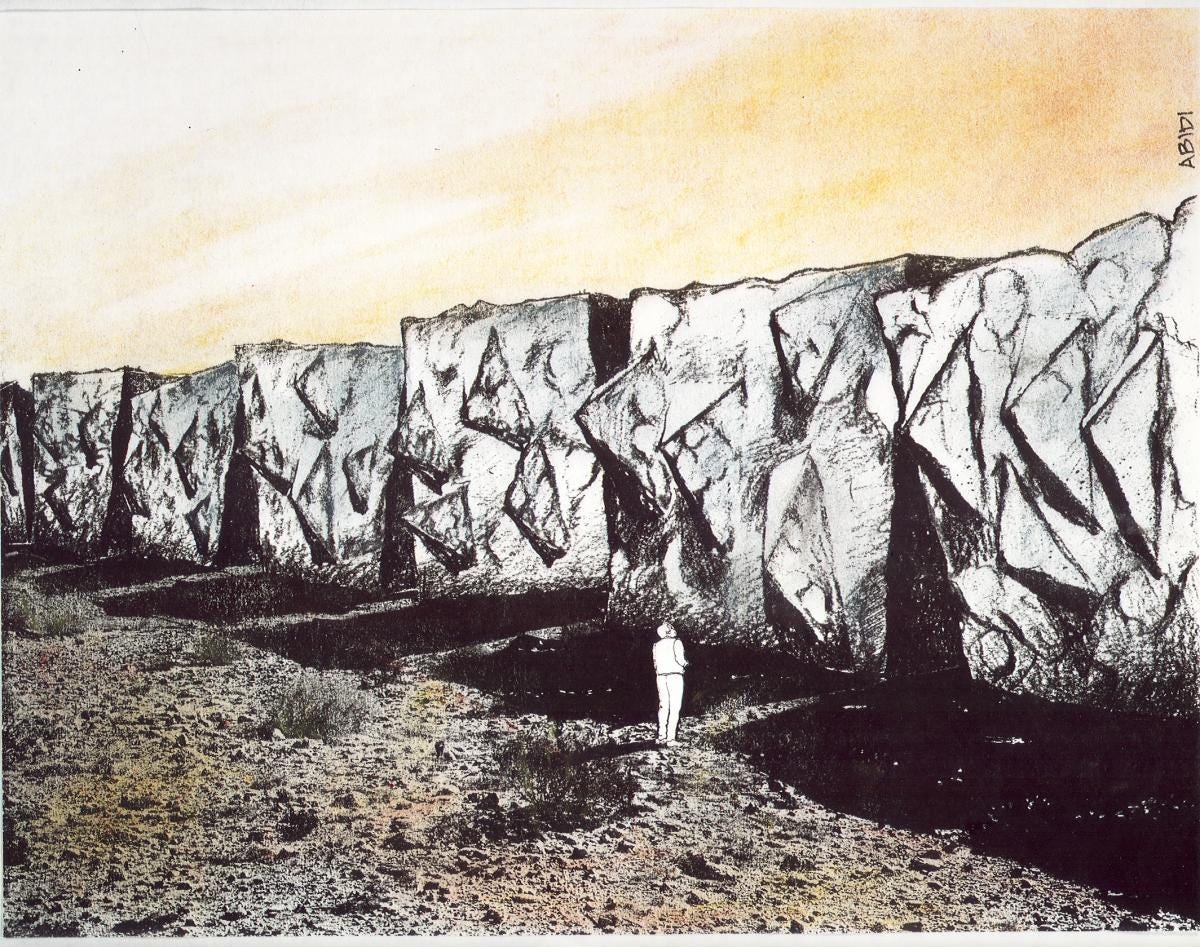

Others went further, anticipating the treasure’s magnetic pull. They proposed architecture that would physically deter people’s progress—the most startling concept I came across, entitled Black Hole, was a dark masonry slab designed to absorb the sun and project its heat as a deterrent.

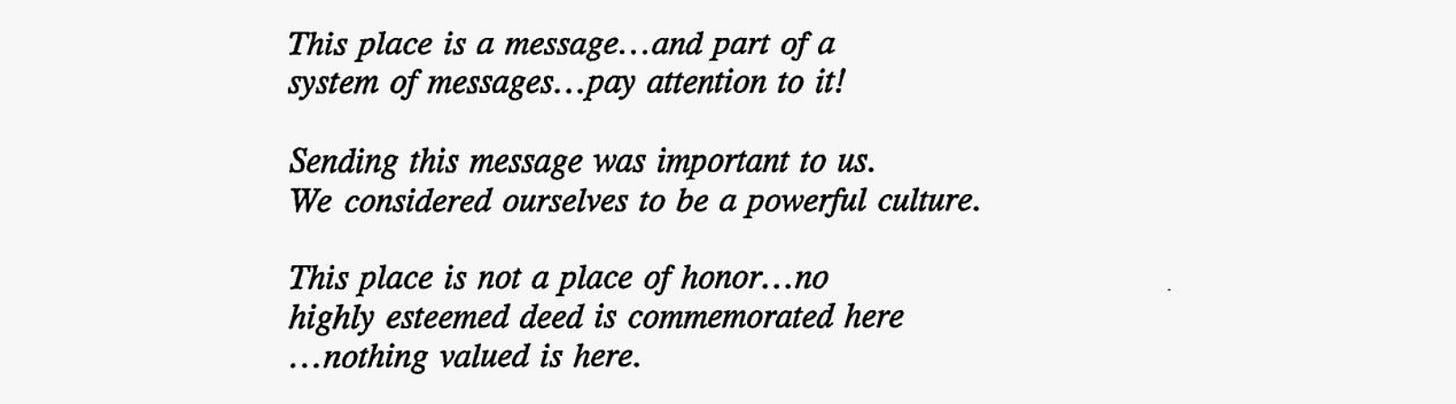

Longtime nuclear waste warning concept: Mike Brill, Drawing: Safdar Abidi; read more here

My favorite resulting solution to the problem was a written message. Linguists carefully evaluated word choice with the intention of making a sign as clear and as simple as possible. (Isn’t that the goal of most linguists? To break signs down into their clearest components?) If ever implemented, a Rosetta Stone would be built into the message, and the text would be translated into every UN written language. As far as I can tell, this proposed message has not been made standard, but the diction feels that way—like an institutionalized dispatch, ringing with finality.

From a report, Expert judgment on markers to deter inadvertent human intrusion into the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant; read more here

Hostile architecture. Long-term nuclear waste messages. These concepts arose out of an almost impulsive generosity towards an unknown people.

What kind of safeguards are we bound to create for future generations? When (and if) our civilization falls apart, how do we warn the future about the threat that will remain? What do we owe potential alien visitors, or our ancestors who have forgotten how to speak with us?

I read a Forbes article that analyzed all of this. Following his description, the writer opined that it was all a colossal waste of time and resources. He believed no one would ever forget our language, or that no one would ever discover the strongholds, or that our future problems would outweigh whatever threat these hypothetical future encounters would pose.

Script of Arrival (2016); read more here

But in his haughty logic, I think he forgot that our society is more about narrative than about logic. We are devoting our time and effort to solving this problem because we want to imagine a future. We seek out these stories in response to the current global state of anxiety over war (which has been present in every war-torn country for all of time, which has only penetrated the American consciousness fully at this point because there are holes widening in the hodgepodge story of our bloated empire) and climate change (which only takes a single academic course to roughly understand as a real and immediate crisis, and which hundreds of billionaires continue to disregard in favor of their own death drive) and poverty (the world’s richest 26 individuals now possess more wealth than the poorest 3,800,000,000 human beings on the planet, and I have viably no power to do anything about it).

It seems near impossible to force those in power to let go of it, for the sake of our survival. An oil corporation will never willingly abandon its oil. Corporations are people—they drive greed into their owners, they wish to evolve and survive and grow like a cancer until they eat up the very people that allow it to exist. How are we ever going to destroy them by relying on reality and logic alone? Reality, as it exists, is stacked against us.

Longtime nuclear waste warning concept: Mike Brill, Drawing: Safdar Abidi; read more here

The entrance to Another Generosity was five feet wide and three feet tall. You had to crouch to enter. But it was cushy and glowing softly, and you wanted to go in and find out what it was like in there. Upon my turn, I squatted and moved forward until I could stand up inside the structure.

It narrowed at the top, but was spacious enough for you to move around. It made me feel like I was a Borrower being carried in a filmy plastic bag full of inflated lights. You could peer out to the museum in certain places, but no one seemed to know they could look within. I placed a hand on the insides of the thing and laughed. I felt free to laugh, that no one was watching me inside this piece of art.

I want to live in a future where we envision a kind of connection between us and an unknown. I want to think about those kinds of things, even if it ends up only being an exercise for myself. There is a generousness there, in the project of making a connection that might not be entirely productive. That thread is one that I want to follow.

Photograph by Allison Denoble

Additional Reading & Rabbitholes:

Another Generosity (art piece description)

Long-time nuclear waste warning messages (wikipedia article)

Arrival raises profile of linguists (article about Arrival)

A Message to the Future (design brief; contains various longtime message artworks)

‘Containment’ Envisions Nuclear Waste Storage 10,000 Years In The Future (article about documentary film)

Thank you to my friend Chloe for encouraging me to write this piece.